The Painter Who Kisses the Ground

Critical text by Zohar Bernard Cohen

The life and work of Oded Feingersh are divided into four central chapters that reflect a continuous movement between personal identity, collective history, and a developing visual language. Colour and material in his work are not merely aesthetic tools, but carriers of symbolic meaning. They are absorbed into the image in the same way that content is absorbed into memory. The phantoms, the painted narratives, the landscapes, and the café scenes offer a multilayered reading of a charged reality, both personal and national.

The Phantoms, among the earliest works in Feingersh’s artistic path, stand at the centre of this exhibition. These paintings place fear at their core: fear of immigrants, fear of refugees fleeing violence, and fear of believers in an abstract divine entity following the decline of faith in the gods of the great Greek and Roman empires. The imagery draws from the pagan world, gods of sun, water, and fertility, and from sacred objects around which temples and sites of worship are built as spaces of power, belief, and communal gathering.

Feingersh’s biographical background is deeply interwoven with his work. His father fled the Caucasian forces of the Russian Tsar that attacked Jewish communities in Ukraine. His mother also came from a family of refugees persecuted for their Jewish faith. Their story is one of searching for territory, a liminal zone between East and West. The Land of Israel, imagined as a “villa in the jungle,” became both ideal and utopia. It was a space of immigrants from Europe, Africa, India, and the Americas, united by the monotheistic faith from which Western culture emerged.

The War of Independence in 1948 marked a significant shift in consciousness and reversed the image of the Jew as an eternal victim. The Jew bearing arms stood in sharp contrast to the diasporic figure, and alongside this reversal, antisemitic stereotypes intensified, from The Protocols of the Elders of Zion to conspiratorial images of control and domination.

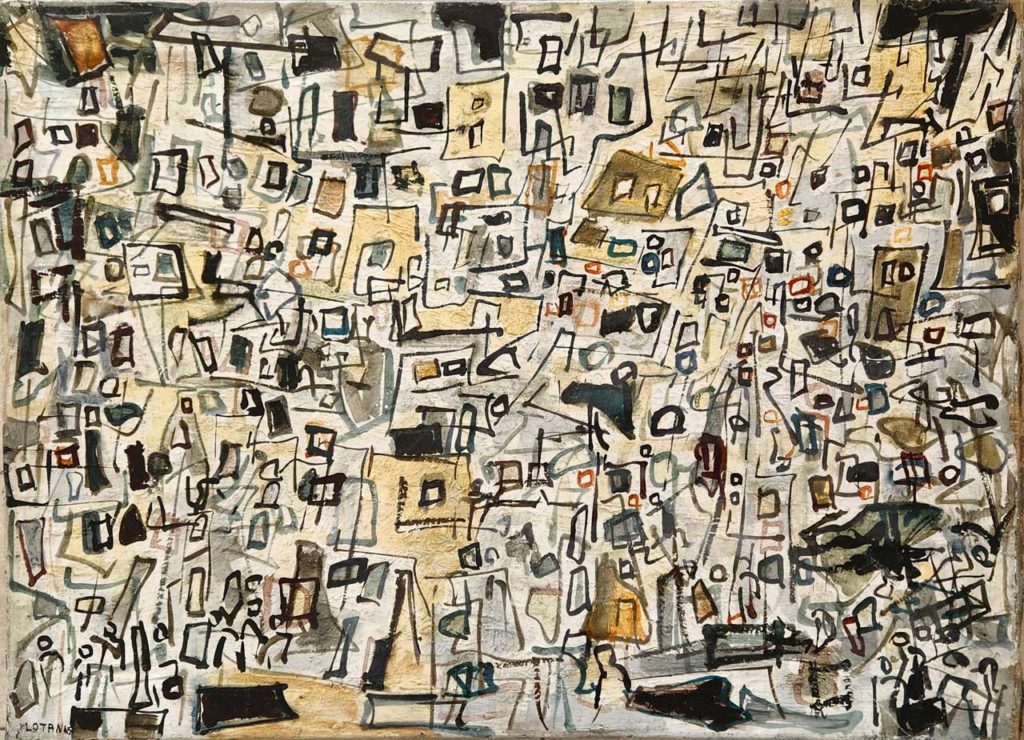

In his later works, Feingersh depicts an urban apocalypse, a modern Tower of Babel. Buildings, cities of burial, and chaotic accumulations of stone merge into a Kafkaesque visual language reduced to black and white, light and dark. It is a twilight moment in which the human figure appears as an amorphous, demon-like being defined by two staring eyes. These figures survive within a violent megalopolis while the shadow of fear, embedded in the DNA of Jewish existence, continues to hover above the city.

In the second phase of his work, Feingersh turns to painted narrative, a visual field in which the human body is conceived as the centre of sin and simultaneously as an arena for the perversions of modern culture. If the body is the locus of desire, it becomes possible to trace through it the passions, anxieties, and deviations of the age.

This is a world of European decadence. It recalls Berlin between the two World Wars, the spirit of Cabaret, the mockery of militarism, and German Expressionism as a psychological response to the collapse of order. Cultural schizophrenia, gender ambiguity, unisex identities, and beauty contests for both women and men coexist in a space where identity itself becomes performance.

Alongside this appear symbols of excess and display. Yachts and luxury cars, recreational drug use, the collapse of the traditional family, and the seduction of the “good life,” La Dolce Vita. This is Hollywood for artists, a sphere in which entertainment, violence, and glamour converge into a single deceptive image.

Within this context, Feingersh paints American superheroes against the backdrop of the World Wars as an allegory for a culture of instant imagery and accelerated consumption. The impatience of younger generations with long-form reading, such as War and Peace by Fyodor Dostoevsky, is condensed into a single image. An airplane drops bombs in a painting by Roy Lichtenstein, and the solitary word BOOM becomes a visual summary of modern warfare.

In exhibitions such as Sentimental Pictures with Atomic Bombs and Two American Agents in the War against International Communism, Feingersh constructs a provocative and Kafkaesque universe. Jesus fights cowboys. Anxious parents shoot the suitors of Venus rising from the sea. Machines designed to enlarge women’s breasts appear. Figures operate like actors in a theatre without text or director. This is a world of grotesque excess in which reality itself appears as an ongoing farce.

Works from this period were exhibited in major museums in Israel, as well as in spaces outside the institutional framework. These include the Museum of Black Magic in Lviv, Ukraine, and the Artbooka tattoo studio, one of the most influential centres of contemporary tattoo and visual culture in Israel. The movement between museum and popular space highlights a central axis of Feingersh’s painted narratives, the blurring of boundaries between high art, mass culture, and visual politics.

In the third phase of his work, Feingersh returns to landscape painting. After abandoned cities, images of destruction, and urban apocalypse, an opposing movement emerges. In place of ruin, hope begins to take form. The landscape ceases to function as background and becomes a conceptual position, almost a declaration of a possible future.

In a Western world marked by demographic stagnation and decline, where families often have only one or two children, Israel presents a different reality. It is a space that continues to believe in continuity, creativity, and life, even in the face of trauma and violence. Within this context, a Jewish universal consciousness is present, reflected in an intellectual and cultural contribution that far exceeds geographic boundaries and persists despite a history of persecution.

Feingersh’s landscapes are not detached from the world. They are charged with global political and cultural references. Artists, intellectuals, and thinkers move between countries, ideologies, and collapsing economic systems. Statues are shattered, symbols replaced, ideals eroded. Even the iconic image of the family picnic changes. It is no longer an idyll of untouched nature, but a suburban space, a transitional zone, a parking lot beside a gas station. Nature itself becomes a cultural mediator.

This transformation is also evident in Feingersh’s use of colour. He abandons the traditional European palette of browns, greys, and olive greens and adopts the primary colours of print, advertising, and the industrial world. Yellow, red, blue, and black dominate. There are no intermediate tones, no romantic hierarchies, and no academic rules. Colour functions as a direct and uncompromising statement.

Within the landscapes, a vision of future art takes shape, art bound to the ground, to place, and to the experiencing body. The immigrant does not approach immigration offices to check a visa, but kneels and kisses the ground. The sight of the flag brings tears, not as pathos but as recognition of belonging. The landscape becomes action, gesture, and identity.

After these optimistic landscapes, Feingersh returns to everyday life and to café scenes. Human figures, chance encounters, and urban routines fill the canvas. The paintings become saturated with colour, movement, and lightness, yet beneath the surface pulses the same primordial fear from which the journey began. This fear does not disappear. It is concealed and transformed into narrative.

Once, Oded Feingersh was asked how he defines himself. His answer was simple:

“I believed I was a man of the great wide world. I met artists larger than life, experienced, applause at my exhibitions, and touched the sky. But in the end, I returned home. I am a small Jew from the Old City of Jerusalem.”

Feingersh’s work unfolds throughout the exhibition as a conscious arc. It moves from primordial fear to the body, from the body to the image, from the image to the landscape, and from the landscape back to the human figure. This journey is not linear but circular. It seeks recognition rather than resolution.

Fear, present at the outset as an existential phantom and historical shadow, does not vanish. It changes form. It is absorbed into the body, fragmented in painted narratives, seemingly calmed in the landscape, and returns in everyday life. It appears in café conversations, in small gestures, and in the human gaze. Feingersh’s art offers no illusion of redemption, but a sober awareness of belonging.

Between religious myth and pop icon, between urban apocalypse and open fields, between exile and home, Feingersh articulates an artistic position that refuses to choose a single side. He holds contradiction intact, the global image and the local ground, cynicism and belief.

The Painter Who Kisses the Ground is not a romantic gesture. It is a charged and almost political act that defines belonging through body and material. The ground is not an abstract symbol, but a living surface that absorbs memory, trauma, and hope.

This exhibition presents Feingersh not only as a critical observer of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, but as an active witness. He is an artist who recognizes the fragility of existence and repeatedly chooses to return, to paint, and to tell stories. Not to escape fear, but to live with it.

Zohar Bernard Cohen

Tel Aviv, 2025.